SomnusNooze

Have you ever noticed how difficult it is to diagnose hypersomnias? Maybe you’ve wondered if a narcolepsy type 2 diagnosis is actually idiopathic hypersomnia (IH) or vice-versa? Have you questioned whether the diagnosis is IH “with long sleep time” or without? (What is long sleep time, anyway?) Even worse, perhaps a hypersomnia disorder is truly present, but when the sleep test results come back, they don’t meet the criteria for any diagnosis.

Patients and clinicians aren’t alone in asking these questions and struggling with the challenge of reaching an accurate diagnosis. A team of European hypersomnia researchers and clinicians, including HF’s MAB member, Dr. Gert Jan Lammers, studied these issues in light of the latest research and wrote a proposal for new diagnostic criteria for central hypersomnias. The journal article, “Diagnosis of Central Disorders of Hypersomnolence: A Reappraisal by European Experts”, begins by describing several limitations of the International Classification of Sleep Disorders, 3rd edition (ICSD-3), which provides the current diagnostic criteria for disorders of hypersomnolence. (For an overview of current diagnosis methods, see our Classification of Hypersomnias web page.) These limitations include the following:

- Some disorders are diagnosed based on symptoms, while others are diagnosed using physiological measurements.

- There is no way to distinguish the severity or certainty of diagnoses.

- There is no inclusion of a mechanism to measure long sleep time.

- The multiple sleep latency test (MSLT) is relied upon too heavily. There are potential drawbacks to using the MSLT as a diagnostic tool, as it can lead to misdiagnosis and may not be reliable over time. Also, although the MSLT has been validated in healthy volunteers who have been sleep deprived and in some small studies of narcolepsy type 1 diagnosis, it has not been validated for people with other sleep disorders, including idiopathic hypersomnia and narcolepsy type 2.

Because the current system of diagnosis is limited in many ways, any new diagnostic criteria must be able to address these limitations in order to help patients who do not currently fit into any diagnostic category. These patients therefore either do not receive a diagnosis or are misdiagnosed, but their lives are still impacted by debilitating excessive daytime sleepiness.

What Do the Authors Propose?

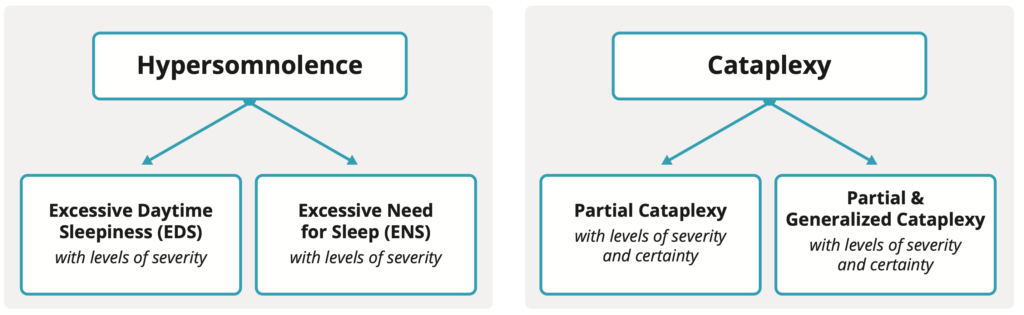

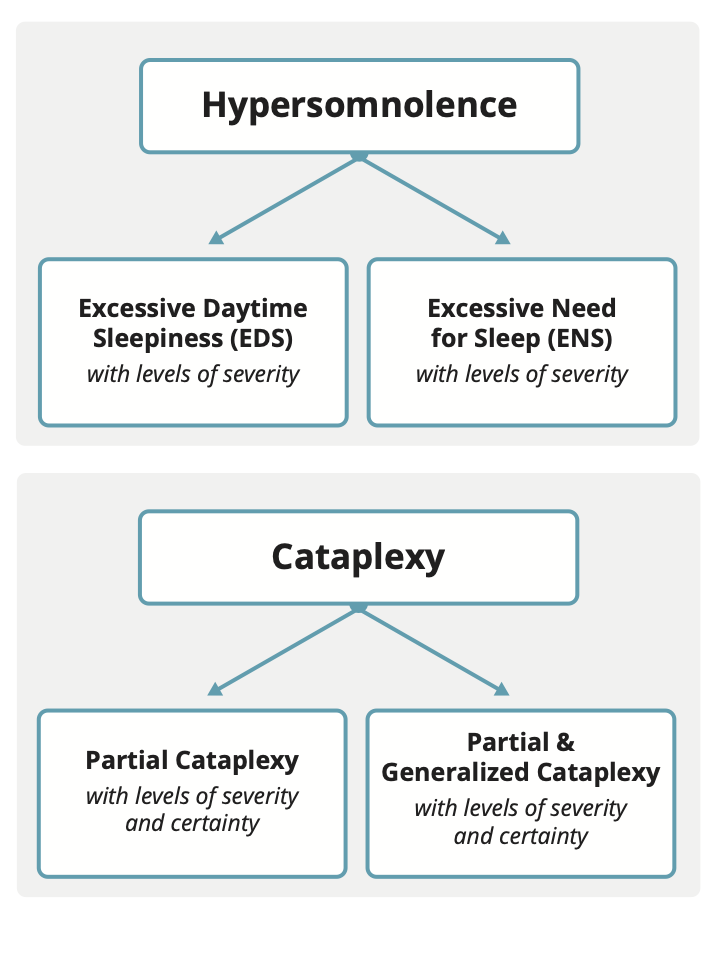

First, the authors break up the term “hypersomnolence” into two forms, excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) and excessive need for sleep (ENS). Several symptoms are listed, but briefly, EDS is characterized by a feeling of being sleepy and having trouble staying awake for most of the day. ENS is characterized by needing more sleep than the average person daily (at least 10 hours). EDS and ENS are further divided by severity.

Cataplexy is divided by the presence of partial cataplexy only the presence of both partial and generalized cataplexy. It is further divided by severity and certainty.

Next, other potential primary causes of hypersomnolence must be excluded as the ONLY cause. First, any sleep deprivation must be treated with sleep extension; if hypersomnolence resolves, there is no need for further evaluation. Second, any sleep apnea and/or circadian rhythm disorders must be treated; if hypersomnolence resolves, there is no need for further evaluation. It is also important to exclude other potential secondary causes of hypersomnolence, such as autoimmune conditions; again, if hypersomnolence resolves with treatment, there is no need for further evaluation for a central disorder of hypersomnolence.

Of note, the diagnosis of central disorders of hypersomnolence is further complicated by the high frequency of comorbid conditions, such as depression, anxiety, chronic fatigue, and attention disorders. Additionally and importantly, some of these conditions, particularly attention disorders, depression and anxiety may not be truly comorbid but may instead be manifestations of living with chronic EDS.

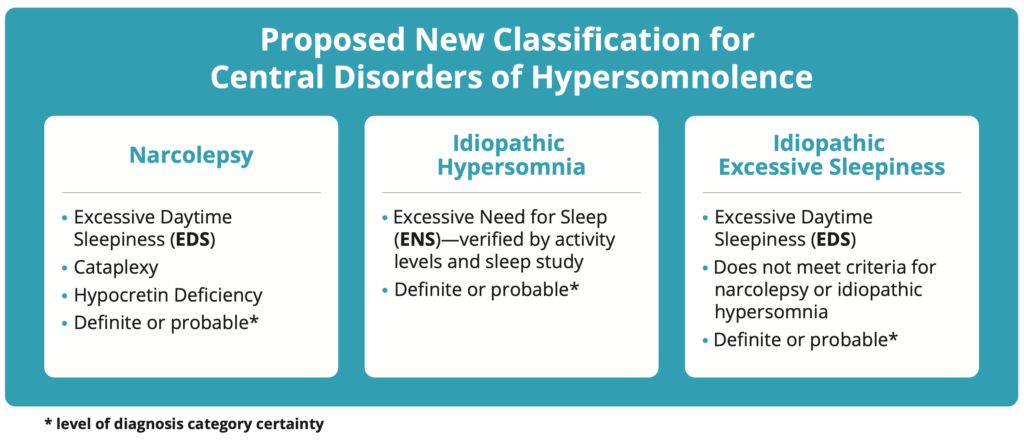

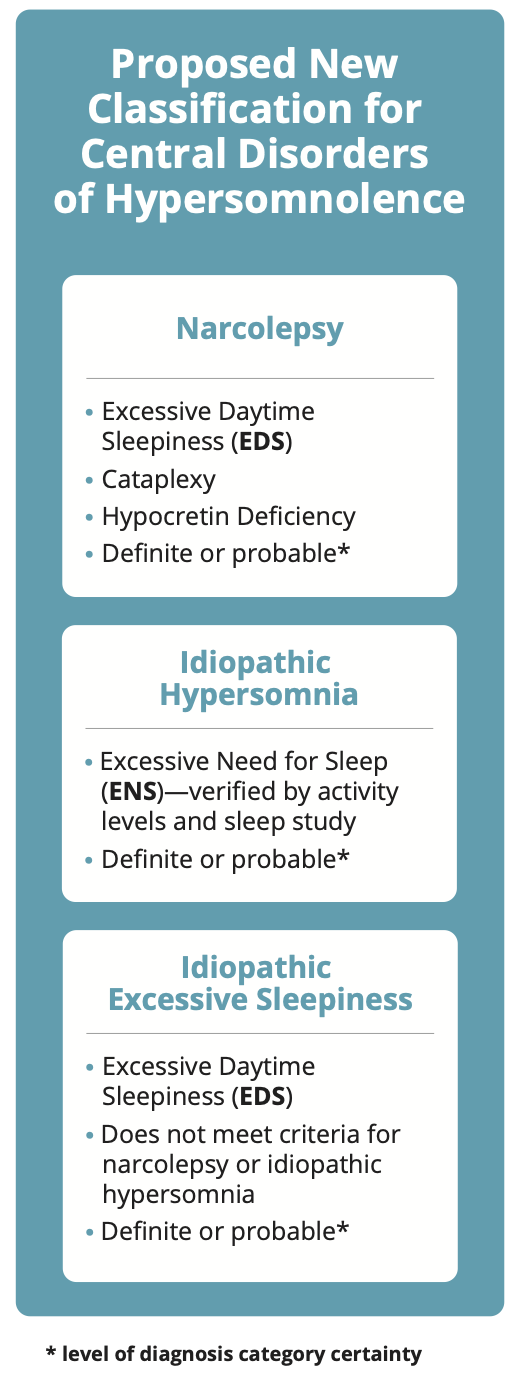

The following three diagnostic categories to classify central disorders of hypersomnolence in adults are then proposed, each with their own criteria:

- Narcolepsy – This new narcolepsy category is only for those who currently have a narcolepsy type 1 diagnosis due to the presence of cataplexy or demonstrated low levels of hypocretin in cerebrospinal fluid.

- Idiopathic hypersomnia – Although there are several diagnostic criteria that must be met, this idiopathic hypersomnia categorization is primarily defined by the presence of ENS, or demonstrated need for excessive sleep over a 24-hour period.

- Idiopathic excessive sleepiness – This new category presents with EDS but not ENS. People who currently have a narcolepsy type 2 diagnosis or IH without long sleep time are likely to fall here.

Based upon all of the documented symptoms and test results, these categories are then further broken down into two levels, definite and probable, which refer only to the level of certainty of the diagnosis category/name (and not to the existence of the illness itself). Since current sleep testing protocols do not capture total sleep time over 24 hours, which is needed to determine if an idiopathic hypersomnia diagnosis is definite or probable, the proposal recommends the development of multi-day/night sleep studies, some of which are already used in a few European sleep centers. Below is a simplified diagram of the proposed new classification system.

What Are the Authors’ Conclusions?

This new classification for central disorders of hypersomnolence is intended to improve clarity and allow diagnosis and treatment for patients experiencing significant hypersomnolence who do not meet the current diagnostic criteria of the ICSD-3. The authors state that their proposal addresses many concerns with the ICSD-3 diagnostic criteria, including:

- Diagnosis will be based on self-reported symptoms rather than neurobiological markers, which is necessary because the underlying cause of hypersomnolence is currently poorly understood, and neurobiological markers are unavailable for most diagnoses.

- There is an emphasis that other potential causes of hypersomnolence must be excluded prior to diagnosis—especially sleep deprivation, obstructive sleep apnea, circadian rhythm disorders, and secondary causes such as autoimmune disorders.

- There is an understanding and allowance for the frequent existence of comorbidities, such as chronic fatigue and depression, keeping in mind that some apparent comorbid conditions may instead be manifestations of living with chronic EDS.

- Extended sleep studies provide a way to measure and account for long sleep time.

- Allowing the results of the MSLT to change over time without necessarily changing the diagnosis can help patients maintain access to their treatments.

Next Steps

Updating the diagnostic criteria for the ICSD-4 is still a few years in the future. Researchers and clinicians across the globe continue to discuss this proposal and others, along with the implications of adopting any new diagnostic criteria and diagnosis names. Future implementation of a new system will come with several potential obstacles, including changing current medical/diagnostic practices and changes to insurance coverage. For example, the cost and practical difficulty of offering multi-day/night sleep studies to diagnose ENS make it unlikely to become widely available. Also, if the European proposal is implemented, it is unclear whether treatments approved under the current diagnostic categories will still be approved if a patient’s diagnosis name changes. Additionally, will someone with a “probable” level of diagnosis category have a difficult time getting their treatment covered under insurance? As noted above, that would be a misinterpretation of the use of “probable” in this proposal, which only refers to the level of certainty of the naming of the diagnosis, not to the existence of the illness itself. It is routine throughout all medical fields to treat the most likely diagnosis. If/when that most likely diagnosis changes (due to symptom evolution, new test results, etc.), then the diagnosis name and/or certainty is updated to reflect those changes. While limited application of the proposed classification in research studies has already begun in Europe, it will take time to finalize the next version of the ICSD diagnostic criteria and to implement changes in sleep medicine clinics and the World Health Organization’s ICD coding (which helps define health insurance payments in the U.S.).

For more information on the European proposal for diagnosing hypersomnia:

- Lammers, Gert Jan, et al. “Diagnosis of Central Disorders of Hypersomnolence: A Reappraisal by European Experts.” Sleep Medicine Reviews, vol. 52, 2020, p. 101306, doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2020.101306. Free Abstract and Request Full Text.

- Webinar recording of “Diagnosing Hypersomnia Differently—A European Proposal.” The primary author of the journal article, Dr. Gert Jan Lammers, describes the difficulties of diagnosing hypersomnias and how the European proposal is designed to provide a more inclusive and accurate system of diagnosis.

2021 May – Dr. Gert Jan Lammers – “Diagnosing Hypersomnia Differently: A European Proposal” – a Hypersomnia Foundation Virtual Webinar

We are grateful to Jodi Godfrey, PhD, for summarizing this journal article.

Approved by Gert Jan Lammers, MD, PhD, HF Medical Advisory Board.