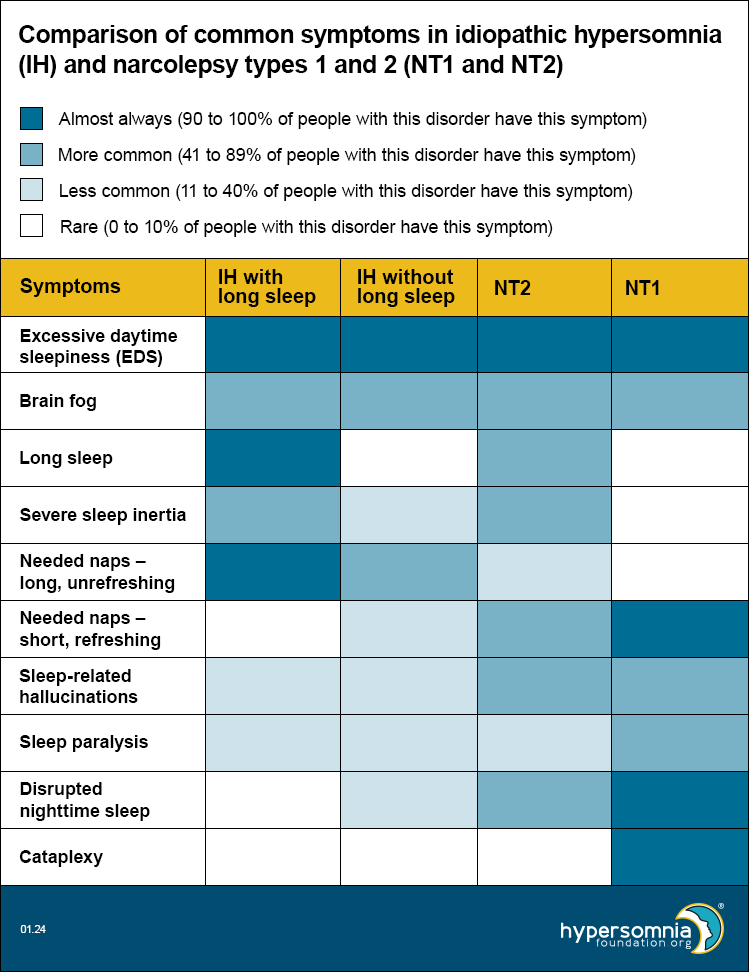

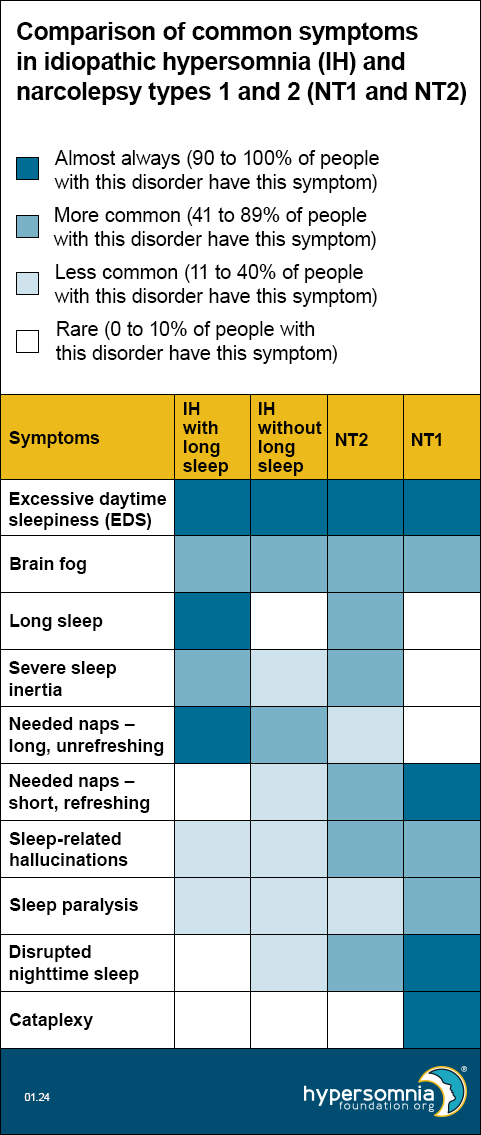

Idiopathic hypersomnia and narcolepsy types 1 and 2 have some similar and overlapping symptoms. For example, all of these disorders cause excessive daytime sleepiness and brain fog. Other symptoms are more common or less common in people who have these disorders.

Idiopathic hypersomnia and narcolepsy types 1 and 2 have some similar and overlapping symptoms. For example, all of these disorders cause excessive daytime sleepiness and brain fog. Other symptoms are more common or less common in people who have these disorders.

The table below compares how common certain symptoms are in:

- Idiopathic hypersomnia (IH) with long sleep

- IH without long sleep

- Narcolepsy type 2 (NT2)

- Narcolepsy type 1 (NT1)

This table can be helpful in thinking about which type of sleep disorder you may have. Because many researchers think IH without long sleep and NT2 may be the same disorder, we’ve placed them next to each other to help you compare them more easily.

The colors in the table show how common it is for people with that disorder to have that specific symptom. The legend tells you what each color means. For example, dark blue means people with that disorder almost always have that symptom. The numbers show what percent (how many people out of 100) of people have that symptom.

Symptom descriptions

- Excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) — A strong daytime sleepiness or need to sleep during the day, even with enough sleep the night before

- Brain fog — Feeling mentally sluggish or fuzzy, confused, forgetful, or unable to focus

- Long sleep — Needing at least 11 hours of sleep per 24-hour period (including naps) or more than 9 hours at night (or whenever you sleep the longest)

- Severe sleep inertia (or sleep drunkenness) —

- Difficult to wake — may need multiple loud alarms or to have a supporter help with waking

- Struggling to wake up fully, often with an overwhelming desire to go back to sleep

- Feeling disoriented, confused, or irritable

- Having poor coordination

- Doing tasks without realizing it

- May last for a few hours after waking up

- Needed naps —

- May be hard or impossible to avoid

- In IH, usually long (more than 1 hour), unrefreshing (non-restorative), and may make people feel even worse

- In NT2, usually short and somewhat refreshing (restorative)

- In NT1, usually short and refreshing

- Sleep-related hallucinations (or waking dreams) — Seeing, hearing, feeling, or smelling something that isn’t actually there while you’re falling asleep or waking up

- Sleep paralysis — Inability to move or speak, which happens while falling asleep or waking up and lasts for a few seconds to minutes

- Disrupted nighttime sleep —

- When you wake up many times in a night

- You may not notice when this happens, but it can make your sleep less restful and you may wake up feeling tired and unrefreshed

- Your sleep studies may show arousals (wake-ups) from sleep or a high number of shifts (changes) between different stages of sleep

- Cataplexy — A sudden and temporary episode of muscle weakness, usually triggered by strong emotions

Learn more

Visit our web pages:

Refer your doctors to our web page for them: “Diagnosis, classification, symptoms, and causes of hypersomnias.”